by Devyani Chhetri

Devyani Chhetri is the South Carolina politics reporter for the Greenville News and has written extensively about the intersection between faith and politics. She is a Boston University post-grad and has previously worked for the Sun Chronicle in Massachusetts.

Two weeks after he publicly came out as gay, former Bob Jones University student Andrew Pledger heard a knock on his door.

It was his final semester of his senior year. He was resting in his dorm room during the evening hours.

A university official stood outside and told the then-21-year-old to make his way to the official’s office for a meeting. He could see the writing on the wall. He knew he was about to be expelled from the private, evangelical institution.

His inclination was correct.

A year later, in the first week of July 2023, Pledger sat in his Greenville home with 17 former Bob Jones University students and two faculty members. They were, collectively, attempting to flesh out what they had in common.

Several of the attendees belonged to the LGBTQ+ community and went to the university at different points over the past three decades. Most of them grew up in fundamentalist households, were homeschooled, or had parents who met and married while at the Greenville-based university.

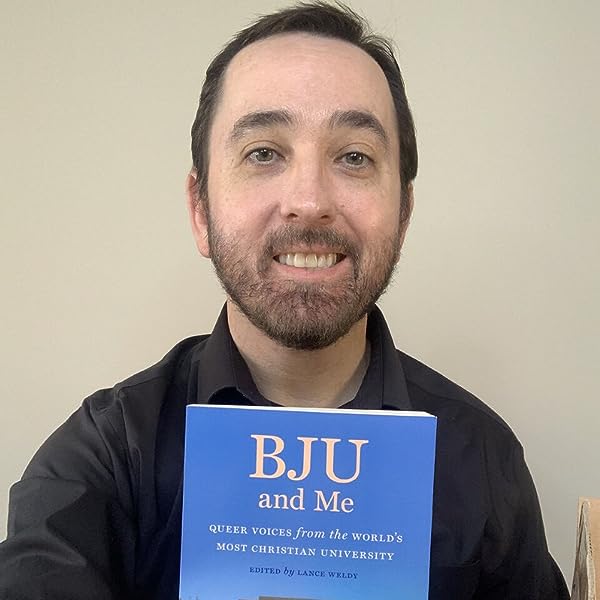

Lance Weldy is a former Bob Jones University student who edited a collection of personal essays by LGBTQ+ alumni, BJU and Me: Queer Voices from the World’s Most Christian University. He said following a similar path as his parents who met at the university felt like the obvious choice. “BJU is kind of the reason I exist,” Weldy said.

But in the years following their departure from the university, the group of former students have individually sought to create records of the environment at Bob Jones University.

In court documents, blog posts and the collection of personal essays, former students say the university’s disciplinarian approach in preserving its steadfast opposition to same-sex relationships and secularism came at a cost ― to the students themselves.

“Trauma really affects how you relate to people,” Pledger said, adding that the university, which receives federal funding, had religious policies that led students on a path of isolation. He added the atmosphere marginalized students at risk of harassment.

Pledger starts podcast: ‘Surviving Bob Jones, a Christian Cult’

Pledger, who now works as a social media manager, is producing a podcast in collaboration with more than 10 former BJU staff and students. The first four episodes were released Aug. 23. The podcast seeks to explore the roots of fundamentalism and how its restrictive policies leave indelible marks on former and current students.

Bob Jones University did not respond to requests for comment on Pledger’s podcast or this article.

In his own time on the Wade Hampton Blvd. campus, Pledger said he was bullied by a group of students who used anti-LGBTQ+ slurs and followed him around.

“I felt unsafe, but I could not tell anyone about it because I would be the one who would have gotten in trouble,” he said.

Pledger was always aware of the university’s long history of opposing homosexuality.

In 1980, Bob Jones III, president of the university from 1971 to 2005, said homosexual people should be stoned “as the Bible commands.” Jones issued an apology in 2015, disavowing those comments.

David Diachenko, a former Bob Jones University student and faculty member, resigned in 2006, after coming out as gay. He said the university softened its rhetoric over interracial dating and dress code over the years. However, he believes the university’s official policy related to gender and sexual identity will never change.

“Because they see that as kind of a basic tenet in their interpretation of the Bible,” he said.

The current policy statement on the university’s website says genders are assigned at birth by God.

“We believe God intended heterosexual marriage for the propagation of the human race and the loving expression of healthy relational and sexual intimacy,” the BJU policy states.

The university’s rigorous sermons also continue to indicate where the school stands on cultural issues, said Camille Lewis, a professor at Furman University and a former Bob Jones student and faculty member.

Sermons given by previous leadership, from Steve Pettit to Bob Jones III, have continued with similar messaging.

“It’s not the fact that Jesus has saved us that makes us able to live the Christian life,” Lewis said. “The message is ‘You need to check all these boxes of righteousness in order for Jesus to save you,’ which is a whole different kind (of Christianity). It’s very human-centered, not Jesus-centered.”

Lewis said she and her husband resigned from BJU after the couple resisted a rule that would’ve allowed the campus daycare centers to use corporal punishment on their son. “Hitting a child a tenth of your age and a fifth of your size was so important to this bastion of fundamentalism that it could not tolerate my refusal,” Lewis wrote in a Huffpost Op-ed detailing the denouement of her affiliation with fundamentalism.

“My mothering was offensive to them because I was making decisions that were not with the fundamentalist code of ethics,” Lewis told the Greenville News. “I refused to let them hit my children.”

Lewis said the enforcement of restrictive rules was controlling.

“I’m sure for an LGBTQ+ person that is even more pronounced, prominent and heavy,” she said, adding the university banned her from campus due to her criticism of the code of conduct.

For some students, Bob Jones University, evangelical college often ‘only choice’

Pledger remembers sitting in discipleship groups at BJU where he heard a common refrain against the presence of LGBTQ+ students on campus: “Why are they here?”

Yet for children who grow up in fundamentalist circles, attending a Christian university is often the only choice.

Bill Trollinger, a professor at the University of Dayton, has studied American evangelicalism and fundamentalism extensively. Trollinger explained families raised in fundamentalism gravitated to schools like Bob Jones in search of “safe schools” that toed the line on core issues such as sexuality.

“Schools are between a rock and a hard place,” Trollinger continued. Younger evangelicals are not as anti-LGBTQ, he explained. The schools may have parents and donors who want the school to hold the Biblical line, but they are getting students who may not agree with their parents and are caught wondering, “What’s the big deal?”, he continued. “Even moderate evangelical schools are going through it,” he said.

At 17, Pledger’s parents told him that they would only pay for a Christian school. It served as a reminder that the teen was financially dependent on his parents.

He started searching for Christian colleges with accreditation. Pledger’s parents told him Regent University and Liberty University, both located in Virginia, were “too liberal.”

“It was mainly because of the music they had there,” he said. “In fundamentalist Christianity, you’re really not allowed to listen to music outside of classical or piano or anything with a beat.”

Born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Pledger grew up in an Independent Fundamentalist Baptist (IFB) household, girded by strict rules around his clothing and music choices, as well as traditional gender roles. He was part of a movement that grew as a reaction to modernism in protestant congregations. IFB churches carved their own sect to emphasize a more literal interpretation of the Bible.

Pledger’s parents met at Hyles-Anderson College — an Independent Baptist college in Indiana. Pledger and his two siblings were home-schooled with a Christian curriculum, which denied evolution and espoused the belief that the world was only 6,000 to 10,000 years old.

“I was trained to defend against anyone who said differently and you were taught to always have an answer for everything,” he said.

Fear pervaded his senses. He felt handicapped when he considered the outside world. Pledger said he was a rule follower, loved school and had a sincere desire to get an education.

Pledger said he considered breaking away from fundamentalism before he began his classes at Bob Jones University.

He caught himself disagreeing with his parents, which was a feeling antithetical to everything he had been taught as a child. He was taught to respect authority, no matter what. But he couldn’t.

“I felt so much shame for not feeling the same way,” he said. “And so from then on, I learned to keep my doubts to myself and even learned to just repress them.”

Pledger was a freshman when the university hosted its Gender and Sexuality conference in 2019. Speakers, such as former Dean of Students, Jim Berg, said Christians needed to show compassion and be amenable to listening to people with different experiences. However, Pledger saw “compassion” wrapped in statements where homosexuality was touted to be a side effect of sexual assault or a bad relationship with parents.

Pledger said the conference and his day-to-day discipleship groups reminded him that he would always be seen as an aberration.

When the bullying grew worse and his mental health declined, Pledger spoke to his dorm supervisor in confidence about his sexuality and the struggles he faced at the university.

But his cry for help only prompted more self-blame.

“After (the supervisor) heard about the things I went through, he told me that I was paying for my sins.”

Soon after, Pledger said the supervisor began a session of conversion therapy, “to change his sexuality.”

A fog overwhelmed him.

“I don’t even remember the first session,” he said.

But he remembers his feelings after the session ― the weight on his chest, the shame and the suicidal thoughts.

“There was something in me, my intuition that I had developed enough that was like — don’t do this anymore.”

Pledger kisses goodbye to fundamentalism

Pledger was a semester away from finishing undergrad when he appeared on an Instagram live with an influential ex-pastor, Joshua Harris.

Once upon a time, in the evangelical world, Harris’ name was akin to royalty. In the late 90s, Harris wrote a book called “I Kissed Goodbye to Dating,” which served as a guide for generations of Christian families. The book instructed people to stop dating to avoid pre-marital sex and marriages ending in divorce.

In 2018, Harris rescinded support of his book. In a USA Today op-ed, Harris wrote “The ideas in my book weren’t just naïve, they often caused harm.

Harris later renounced his faith.

“It is very rare for a Christian leader to say, ‘I’m so sorry for the harm that I caused,'” Pledger said, adding that he looked up to Harris.

Last year, just before his expulsion from BJU, Pledger reached out to Harris. He wanted an opportunity to discuss his journey with fundamentalism and the solace he found in visual art.

Pledger had been working on a long photo series in class that followed a man locked away in his room, with just a bed, a cross and a Bible for company. In the series, the man had a key to the locked door around his neck the whole time, but he just couldn’t see it.

“That’s all they have, and for me, it just kind of felt like, internally, that’s how I felt like my childhood was. These things to rely on,” he said.

Harris responded and hosted Pledger for a 40-minute interview that aired on Harris’ Instagram account. Pledger publicly announced then that he was renouncing his faith.

Pledger’s friends warned him that the interview would likely get him expelled. And two weeks later, when the dorm supervisor appeared outside of his dorm room, he was ready. He knew the university “did not allow unbelievers.”

The meeting only lasted a few minutes. The university asked Pledger to withdraw his admission, and he obliged. However, Pledger said he had no regrets. In retrospect, he believes all of his actions hinted that he wanted to leave.

“I got tired of not belonging,” he said.

Note: This article originally appeared in the Greenville (SC) News: Former Bob Jones students, members of LGBTQ community speak out. It appears here by permission of the author.

As a BJU grad 1969, as well as a rule follower, loving school and wanting an education, I, too, learned to bite my tongue and keep contrary opinions to myself–for as long as it took me to graduate. I knew that if I expressed or displayed opinions or behavior outside of policy they would not hesitate to “ship” me in a minute. My question to you was how much of your academic credentials did they allow you to keep or transfer to another school? My only overt signs of rejection was to systematically violate every stated rule in the handbook my final semester, except for those outside of my true character. It was surprisingly difficult to get caught. However, I managed to accumulate demerits one shy of Permanent Campus. It took me at least one year for each one I spent at BJU to decompensate.

Hi, Sharon. I’m a BJU Class of 1990 (BA in English) and 1992 (MA in Public Speaking). I went on to get a Ph.D. from Indiana University, and my experience was exceptionally typical. I was not immediately accepted into IU until I took two 500-level classes to “prove” myself. And then I had to make up all my MA hours. My brother (BJU BA in Bible, 1982; MFA in 1985, MA in Theology, 1984) received a Ph.D. from Ohio State and had to do the same.

This was pretty typical until the mid-00s when diploma mills were running rampant and BJU had no accreditation. Undergraduate degrees were flat-out rejected, and BJU alumni were told to start over. BJU got TRACS accreditation (which is only meh), and it only helped for professional certification. Now that BJU has proper SACS accreditation, this should not happen. But the graduates are so invested in the fundamentalist world, that they don’t usually leave. It’s more insulated than ever because it’s so small.

Hope that helps!

Camille