by Camille Lewis

Camille Kaminski Lewis is currently a Visiting Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. She holds a Ph.D. from Indiana University in Rhetorical Studies with a minor in American Studies. Her book, Romancing the Difference: Kenneth Burke, Bob Jones University, and the Rhetoric of Religious Fundamentalism, was a scholarly attempt to stretch the boundaries of both Kenneth Burke’s rhetorical theory on tragedy and comedy as well as stretch conservative evangelical’s separatist frames. The story of that publication is available at The KB Journal. She is currently working on a manuscript tentatively titled Klandamentalism: Dysfunction and Violence in America’s Most Romantic Religious Movements, while also compiling and editing an anthology – White Nationalism and Faith: Statements and Counter-Statements on American Identity – as part of Peter Lang’s Speaking of Religion book series.

You, Billy Sunday, put a smut on every human blossom

that comes within reach of your rotten breath,

belching about hell-fire and hiccupping about

this man who lived a clean life in Galilee.When are you going to quit making the carpenters

build emergency hospitals for women and girls

driven crazy with wrecked nerves

from your goddam gibberish about Jesus –

I put it to you again:What the hell do you know about Jesus?

Carl Sandburg, “To Billy Sunday”

A hundred years ago, Carl Sandburg was the working man’s poet, the man who named Chicago the “hog butcher for the world.” In the latter part of his life, this “poet of the people” settled a few miles north of me here in the Blue Ridge Mountains. His home is a national park, and we visit often. “Let’s go to the goats,” we’ll say, and we’ll jump in the truck with our Labrador-shepherd mix to pet (and bark at) Mrs. Sandburg’s goats. We climb their stone walls and wander around their chestnut trees. We take turns sitting in Mr. Sandburg’s chair out in the sun where he liked to write. To us, the Sandburgs are like family.

Billy Sunday started his public life in Chicago too, debuting as an outfielder with the Chicago White Sox in 1883. Once a pretty little Presbyterian turned his head, Sunday found religion and began his evangelistic career in the Midwest. By 1917, Sunday’s urban evangelism had made him an unmitigated tycoon, collecting close to $10,000 a week in his crusades—which would be worth almost $200,000 in today’s currency. Even with that midwestern twang, Sunday feels local since I spent half my undergraduate career living in a dormitory named after that pretty little Presbyterian. For me, the Sundays are like relatives too, even if I’d rather not admit it.

Sandburg’s century-old poem confronting Billy Sunday sounds like it could be written for 2020. Sandburg the poet saw through the “bunk” Sunday the tycoon and his descendants are still peddling.

In the middle of a global pandemic which only our great-greats would recognize, with civil unrest that looks like 1965 Selma and on the brink of the Great Depression 2.0 while the nation conscientiously counts down the days to the next election, we white evangelicals breezily commute from home to our white-collar jobs, sipping our iced tea, flaunting social-distancing guidelines all the while casting conspiratorial aspersions on any conclusions from scientists we don’t understand.

We’re no different from Billy Sunday.

We’re in the throes of the same destructive binary that Sandburg confronted and dismantled. We ignore material bodies—living organisms which can get ravaged by viruses, which need protection from armed so-called keepers-of-the-peace, bodies which need fuel and nurture—all in deference to the immaterial ideals of rugged individualism and bootstrap meritocracy.

And Jesus has nothing to do with it.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I had to read Sandburg’s 1915 poem out loud again. Sandburg saw that for Sunday, Jesus was merely an object of a preposition—something to “look at” and then “be all right.” Jesus was a static thing, even a totem.

In contrast, Sandburg puts Jesus as the subject of the sentence. Jesus acts. He acts for others and for free.

Jesus had a way of talking softly and everybody except a few bankers and higher-ups among the con men of Jerusalem liked to have this Jesus around because he never made any fake passes and everything he said went and he helped the sick and gave people hope.

Carl Sandburg, “To Billy Sunday”

Jesus was a living and breathing actor in Sandburg’s poem, an opposite to Sunday who skipped past hardscrabble reality and constricted Jesus within a prepositional phrase. For Sunday, the promise of the next world could distract his listeners into giving him their cash, telling “poor people they don’t need any more money on pay day…all they gotta do is take Jesus” how Billy says. Billy promises that if you ignore current and ugly reality, you’re guaranteed future bounty in the sweet by-and-by.

But Sandburg cuts through Sunday’s humbug: “I ask you to come through and show me where you’re pouring out the blood of your life.” In other words, get real, Preacher. Get your boots dirty. Work with your own two hands rather than warble about future rewards (while piling up hard cash for yourself).

And Sunday’s descendants are still hawking the same bunk.

Early in the pandemic, Dallas-trained seminarian Costi Hinn offered one variation on the Sunday theme. “Grace” is what’s needed in these perilous times. He purrs in the end, “choose love.”

Sounds lovely, doesn’t it? Who wouldn’t want some love right now? Who doesn’t need a little social grease for the machinations of life in the middle of civil unrest?

Putting on Sandburg’s spectacles, however, clarifies what this century-old narrative blurs. Look who is chiefly doing the action in Hinn’s text. He’s talking with “the team” which is, let’s be honest, the white male pastoral staff. These good guys get thwarted by the devil and those with “opinions” which “dominate” and “spiral downward.” Good guys vs. the devil, ministers with grace vs. people with opinions, looking up vs. spinning down—this old Southern duel persists in conservative evangelical narratives, and this one is no different.

To his fellow ministers, this preacher asks his public to “agree to disagree” on science and rise above those trouble-makers who will only “divide our ranks.” Different conclusions in the midst of a pandemic are merely “convictions”—fundamentalist code for pietistic preferences. Do you drink alcohol socially or abstain? Do you worship with a drum set or a pipe organ? Do you watch PG-13 movies or only G-rated family films? These are the kinds of endless conflicts that Hinn groups with the public health realities in a turbulent time. Do you see wearing a mask as “soft” or do you see refusing a mask as “reckless”? Do you participate in congregational singing or do you believe these “super spreader” events must wait for a later date? Do you fly the Blue Lives Matter flag or protest police violence? These conflicts are all the same kinds of “convictions,” and Hinn and his grace-filled white male team stand outside the debate entirely. They won’t get involved. Their indifference to the nitty-gritty is, Hinn claims, “choosing love.”

Like Sunday, they have no skin in the game. Their hands are clean. Their lungs, they presume, are virus-free.

Sure, Hinn admits that he just wants to preserve relationships since “people matter over opinion.” But notice the people who are missing from his story in order to see which relationships matter. There are no scientists, no public health officials, no elderly, no women, no immune-compromised, and no children. There’s one staff member who is on “paternity leave,” cluing us in to the good guy persona we’re supposed to admire.

Hinn doesn’t even mention Jesus.

And now in the middle of the pandemic, octogenarian fundamentalist John MacArthur sounds even more defiant than Hinn. He does start with Jesus, but notice the framing:

Christ is Lord of all. He is the one true head of the church. He is also King of kings—sovereign over every earthly authority. Grace Community Church has always stood immovably on those biblical principles. As His people, we are subject to His will and commands as revealed in Scripture. Therefore, we cannot and will not acquiesce to a government-imposed moratorium on our weekly congregational worship or other regular corporate gatherings. Compliance would be disobedience to our Lord’s clear commands.

Just like Billy Sunday, MacArthur does not make Jesus an actor. Jesus is not doing anything. He simply is—like a totem. And by the third paragraph, Jesus is back to that comfy object-of-the-preposition placement [emphasis mine]:

A father’s authority is limited to his own family. Church leaders’ authority (which is delegated to them by Christ) is limited to church matters. And government is specifically tasked with the oversight and protection of civic peace and well-being within the boundaries of a nation or community.

The whole drama is centered around the white male authority in the family and the church which has been ordained by Christ which acts against government. MacArthur, like Hinn, ignores the vulnerable, the elderly (other 80-somethings like himself), and the scientists.

Consistently in these evangelical narratives, the white male church leaders are the heroes of their own story, the solitary actors. All the others with their convictions are either ugly adversaries or mere scenery, wallpaper on the set of the white ministerial drama, seconds in the duel between preachers and the devil of government.

Sitting here in a Red State which never closed with too-high positivity rates as the country struggles to mourn now nearly 200,000 deaths, all these white male evangelicals seem to be telling those of us with bodies one thing: “shut up.”

In the first version of his Billy Sunday poem, Sandburg ended with “I want blood instead of bunk in my religion.” So gentle neighbors, in the words of that poet of the people sitting from his chair in the Blue Ridge, I ask you: when are you going to quit making us build emergency hospitals for people driven to death’s door from your rhetoric about Jesus—I put it to you again: What the hell do you know about Jesus?

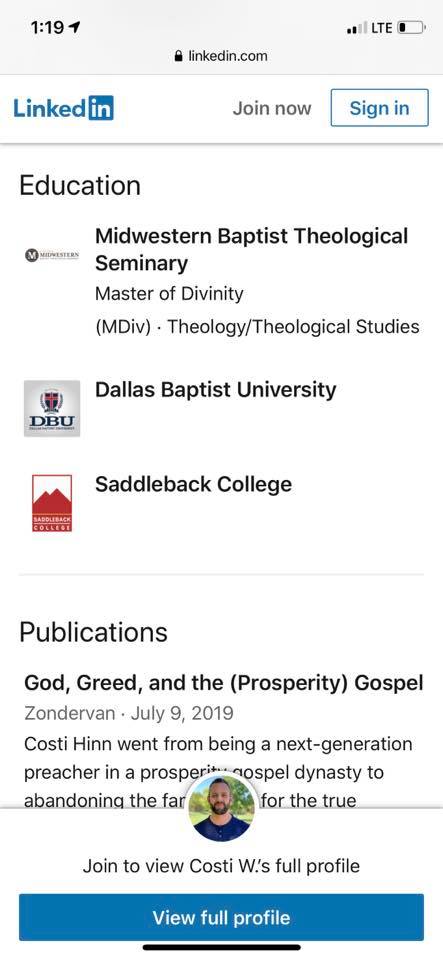

Notice in this image, a screenshot from Twitter, Costi Hinn claims that he: 1. is not a “Dallas-Trained” seminarian, and 2. is not a White male (rather, he notes he is of Palestinian and Canadian ancestry).

His LinkedIn profile lists Dallas Baptist University as part of his education: