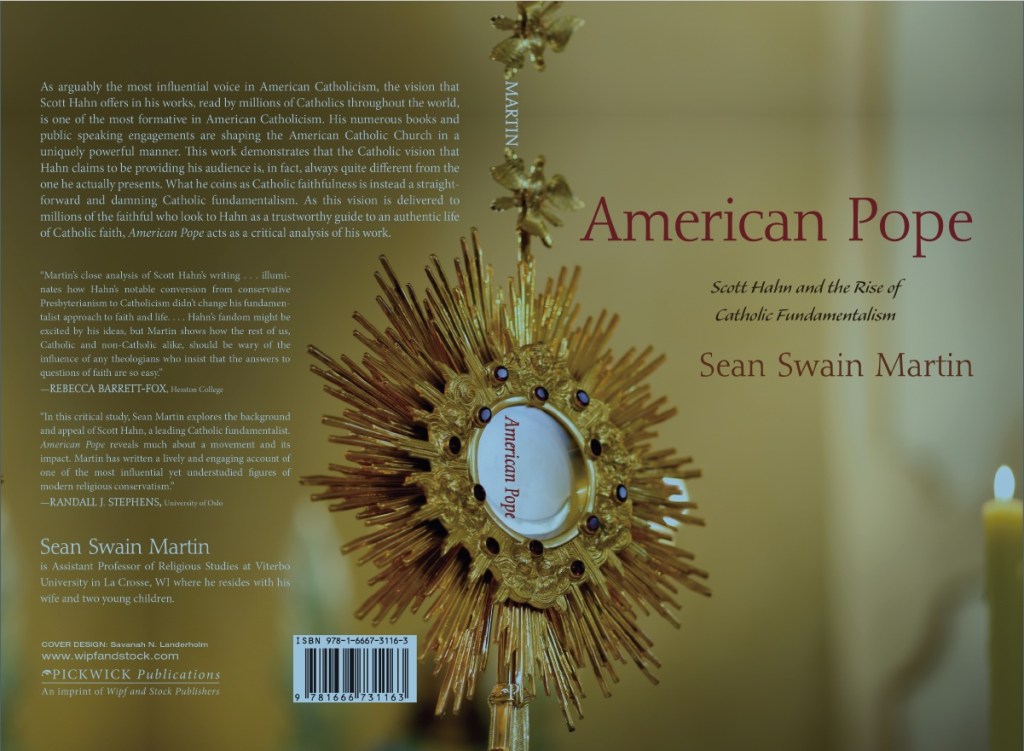

by Sean Swain Martin

Sean Swain Martin is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies and Theology at Viterbo University in La Crosse, WI. His American Pope: Scott Hahn and the Rise of Catholic Fundamentalism (October 2021) published by Pickwick Publications explores the centrality of epistemological certainty in the work of Scott Hahn, attributing to Hahn a specific Protestant fundamentalist approach in his very popular Catholic theological contributions. Sean specializes in American Catholicism, Christian Fundamentalism, John Henry Newman, and early modern philosophy. He holds a Ph.D. and an M.A. in theology from the University of Dayton as well as an M.A. in philosophy from Georgia State University. When not teaching or endlessly grading, Sean and his wife, Beth, are raising two insanely adorable children, Gwen and Milo, and a wildly destructive dog, Luna, in Onalaska, WI.

In many ways, I was wrestling with this subject of American Pope: Scott Hahn and the Rise of Catholic Fundamentalism well before I had ever heard of Scott Hahn. I was raised in southern Georgia in a conservative, evangelical household. We were members of the local Catholic Church, St. Anne’s, until when I was around eight years old and my parents came to believe that the Catholic reading of the Bible was insufficient. They had started attending a neighborhood Bible study led by a Southern Baptist family and became convinced that for the good of their family, they needed to find a church that took the Scriptures more seriously than it seemed our priest did. Within a few short years, we had found a small, nondenominational church to call our spiritual home for the remainder of my childhood.

It was not until I reached college that I experienced my crisis of faith. My home church had taught me that the Bible was the perfect Word of God and that in reading it faithfully, the world was completely laid bare. That is, in reading the Scriptures, again, faithfully, I would see clearly right from wrong, friend from enemy, and good from evil. In leaving my hometown and attending school in Atlanta, my world became exponentially larger very, very quickly. The assurance that the Bible had given me that I was, in a sense, finished with the work of understanding the world and had firmly moved into the mode of saving it, entirely vanished.

Such a development was not just a hiccup in my plan to “seek and save” the world of the lost, it was devastating. In losing my confidence in the absolute perfection of the Scriptures, I saw myself as losing my faith. I stopped attending church services with any sort or regularity. I turned to the Scriptures less and less. I distanced myself from other Christians who still demonstrated vibrant lives of faith. Moreover, I was plagued with the fear that I had damned myself, stepped outside of the perfect love of God, and exposed myself to that side of God that looked a lot like vengeful hatred, but I had always been taught could not be.

In desperation, I turned to a professor who had become something of a trusted mentor. “I don’t understand.” “I don’t know how to fix this.” “I don’t know what to do.” And then, finally, “What would you do?” The answer that this kind and patient mentor offered me will stay with me throughout my life.

My professor told me that he understood what I was going through, that there was value in my current suffering, and that the faith out of which I had forced myself may not have been the faith that I thought it was. And then he told me that he would become Catholic.

In my religious world, there was no group more confused and tragic than Catholics. Their stained-glass churches, Latin hymns, and bejeweled chalices might have a certain aesthetic appeal, but it certainly was not Christian. My affection for this professor was great enough, however, that I began occasionally to visit a local parish. Over the next several months, I began to discover a faith that, to my mind, looked more like the God I still believed in. My questions, doubts, confusion, and even anger were welcomed.

Thus, during my senior year of college, I asked to begin, along with my older brother and sister-in-law who had been directed to Catholicism by the same professor (even if for different reasons), the process of returning to the Catholic faith. And at the Easter Vigil in 2005, I was confirmed in the faith. To my delight, in the old, beautiful parish I had joined, I became confident in my faith, again. Not only did I become more confident in my faith, but I enjoyed my life of faith, particularly going to Mass. Here, finally, I had found a faith in which both my belief and unbelief could rest.

In the years that followed, however, I noticed that there were parts of my newly found Catholicism that began to remind me of the faith of my past. There were those (and sometimes myself) who claimed to have a corner on authentic Catholicism. There were those (and again, sometimes myself) who at times imagined their Catholic faith rendered the world utterly knowable, understandable, and straightforward. While I found in the saints numerous moving depictions of long dark nights of the soul, I continued to long for simplicity in the face of so much confusion and certainty in the face of doubt. The more certain and simple the Catholic faith was depicted, however, the less it resembled the complicated and often fractured faith of the ages that I had joined.

Meanwhile, my parents, who had struggled at the time with my conversion, had been given a copy of a book by a Catholic theologian “who actually explained Catholicism in a way that made sense.” His name was Scott Hahn. This book, Rome Sweet Home, was the recounting of Hahn’s own journey to Catholicism, and, as such, my parents found it helpful in understanding their children’s decision to convert, and eventually led to their own return to Catholicism. While I had never read the book, drowning as I was with the demands of philosophy and then theology graduate work, Scott Hahn became a name that I heard more than almost any other in my different parish communities over the years as someone uniquely gifted at explaining the faith in an accessible and compelling way.

I wrote a philosophy graduate thesis in which I employed Gottlob Frege’s philosophy of language as a response to contemporary defenses of G. E. Moore’s Open Question Argument. It was and is by no means perfect, but I was happy with it and, most importantly, I successfully defended it. Several years later, I successfully defended a theology graduate thesis that argued that Bl. John Henry Newman relied on David Hume’s theory of knowledge to construct his account of the illative sense. There is a lot I would change about it if I could, but I am still proud of the effort and convinced by the argument.

But when friends and family asked me about them as I was writing them, however, they did their best to act interested, but the conversation would quickly turn to other matters. And when my wife, Beth, and I began dating in 2014, she asked if she could read what I had written; while she made a couple of valiant efforts, she never made it all the way through either. She was interested in my ideas and why I felt like they were important, but it was difficult for her to follow all the academic nuances of my theses, given that she did not have the background that I did. I saw value in the work that I had done, but my ideas were not connecting with the people in my life I cared about most. In talking with my friends and family, the conversation would often turn to American life and faith.

Despite how much I had come to love the many different theologians whose works now line my bookshelves, they were not the voices that my friends and family were hearing in the Catholic world outside the academy. That voice was Scott Hahn’s. My parents had his books, and before I met my wife, she and her parents both had his books. Hahn’s books were passed out for free at church during Christmas and Easter. He held large youth, adult, and priest conventions, sometimes multiple times a year. Hahn offered marriage retreats and adult education seminars. And despite the fact that Scott Hahn was the loudest voice in shaping the minds of the faithful, as a doctoral student in Catholic theology, I had no idea what he taught. I had never read a single one of his books. I could not tell you how he envisioned Catholic life and faithfulness. Moreover, when I turned to the theological world, I found that no one else had engaged with Hahn either.

And so the central concern for me in writing American Pope was that, as arguably the most influential voice in American Catholicism, we should understand the vision that Scott Hahn offers in his works read by millions of Catholics throughout the world. Hahn is shaping the American Catholic Church in a uniquely powerful manner and yet, until now, I have been unable to find a single systematic engagement with his thought and work. Thus, American Pope was an attempt to provide just such an engagement, as well as to bring my own philosophical and theological contributions into the wider world of my loved one’s lives of Catholic faithfulness. What I actually argue in the book is that the Catholic vision that Hahn claims to be providing his audience is, in fact, quite different than the one he actually presents. What he coins as Catholic faithfulness is instead a straight-forward and damning Catholic fundamentalism. As this vision is delivered to millions of the faithful who look to Hahn as a trustworthy guide to an authentic life of Catholic faith, it is crucial that we understand, not just the content of his work, but also the perspective with which he approaches theological truth. And while I believe that American Pope succeeds in its critique of Hahn, what I am more interested in is in the book acting as a reminder to those of us in the academy that our Catholic friends and loved ones desire accessible theological insight. Moreover, at present, this largely resides in the work of Scott Hahn and his compatriots, whose audience is massive and whose commitments are not often the best representative of the Catholic tradition.