by Sean Swain Martin

Sean Swain Martin is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies and Theology at Viterbo University in La Crosse, WI. His American Pope: Scott Hahn and the Rise of Catholic Fundamentalism (October 2021) published by Pickwick Publications explores the centrality of epistemological certainty in the work of Scott Hahn, attributing to Hahn a specific Protestant fundamentalist approach in his very popular Catholic theological contributions. Sean specializes in American Catholicism, Christian Fundamentalism, John Henry Newman, and early modern philosophy. He holds a Ph.D. and an M.A. in theology from the University of Dayton as well as an M.A. in philosophy from Georgia State University. When not teaching or endlessly grading, Sean and his wife, Beth, are raising two insanely adorable children, Gwen and Milo, and a wildly destructive dog, Luna, in Onalaska, WI.

Editor’s Note: This post is the second in a two-part series Sean shared about his book, American Pope. You can read part one here.

In the course of trying to make it through yet another season of this seemingly endless pandemic, I binged watched the first season of the new, hit show Ted Lasso. Ted Lasso is the ridiculous story of an American football coach who embarks on a new career coaching an English football team, despite knowing almost literally nothing about the sport of soccer. Lasso, along with his constant coaching companion, Coach Beard, are met in their new roles with ridicule and derision from the rightly outraged Richmond Football Club fans who see Lasso’s hiring as a commitment by the team owner to self-sabotage. While clever in a variety of ways, what is truly compelling about the show is Ted Lasso’s perennial optimism. In the face of a stadium of angry fans chanting their displeasure with him personally, Lasso cheerfully wades through a dismal ninety minutes of football without ever succumbing to the taunts and jeers of the fans. As the season continues, Lasso is challenged, betrayed, heartbroken, and rejected. Yet, through it all, Ted carries with him the constant conviction that he is doing what he truly believes is best.

While compelling, however, this is not what makes Ted Lasso so attractive to me. Ted also carries with him throughout all his adventures (and misadventures) his brokenness, a recognition of his shortcomings, and a commitment to allow himself to be bettered by those around him, friend and foe alike.

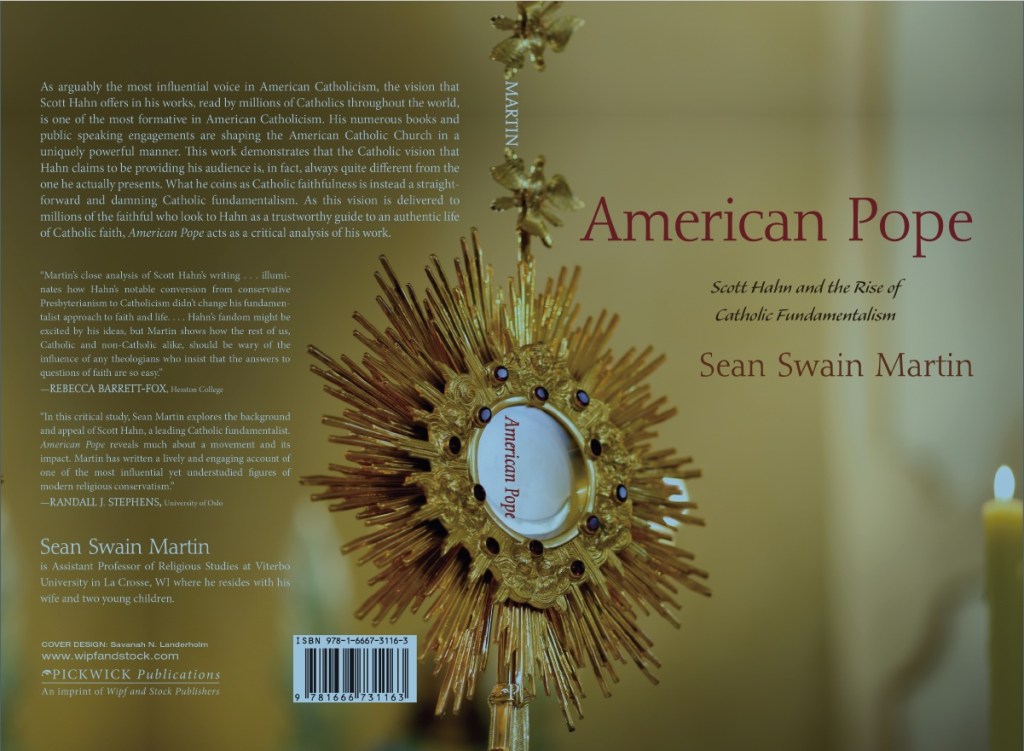

In October 2021, I published my first book, American Pope: Scott Hahn and the Rise of Catholic Fundamentalism with Pickwick Publications, an imprint of Wipf & Stock. While the more academic reviews of the book are still forthcoming, notification of its publication took off on the more Catholic corners of Twitter and I was soon inundated with a host of opinions on the work. Before American Pope even became available for purchase, my tweet announcing the book had been viewed over 120,000 times and interacted with (retweeted, liked, or commented on) more than 35,000 times.

Given Hahn’s popularity, I expected strong reactions to my announcement but as I had never experienced anything like this before, I had no idea what this kind of response might look like. Among the many comments, however, was one that I found quite unsettling. Surprisingly, it was not the private message that I received informing me that the writer was praying for my death so that I may soon experience the judgment of God. It was also not the comment that suggested that I was possessed, nor the one that raised the possibility that I was funded by certain liberal powers to take down faithful Catholics, nor even the host of retweets that assumed that I hated both God and the Catholic Church.

Instead, it was the comment to a supportive retweet, “I hope this author knows what he’s in for. This is going to get bad for him.”

In the weeks that followed and the book began to reach readers, my institution, Viterbo University, received complaints concerning my employment there. Discussions of the book began appearing on Catholic radio stations, blogs, and social media. My book was ridiculed as embarrassing and I dismissed as a jealous, liberal academic who should have never made it through a doctoral program.

Along with all of this, however, I also began receiving emails and private messages from people I had never met thanking me for writing the book.

Such a bizarre experience. On the one hand, my book is riddled with errors, falsehoods, and the most uncharitable of critiques on one of Catholicism’s most faithful scholars. On the other hand, it successfully demonstrates a thoroughgoing fundamentalism in the theology of one of the American Catholic Church’s most prolific writers. I am a failure who should be ashamed of my work, or I have written a good discussion on a topic that needed to be brought to the fore.

So, which is it?

A constant theme in the negative reactions to the book’s publication (not necessarily to the content of the book) is that I must have written the book because I am either jealous of Scott Hahn’s success or because of a hatred for the Church. I am sure that what I say here will not satisfy American Pope’s critics, however, I feel the need to address the question.

There are many reasons that I did not have in mind in publishing my book. First and foremost, I did not write American Pope out of a hatred of Catholicism. It is quite the opposite, in fact. The Catholic Church is my home. It is where I am allowed in my fallenness to be brought together with my family and community to become united with Christ’s goodness in the perfection of the sacraments. It is within the Body of Christ that I have tried, and will continue to try, to offer the little that I can for the good of God’s Church.

The second charge often leveled against me is that I wrote American Pope out of a jealousy for Scott Hahn’s success. All I can offer in response is that I have been fortunate enough to have been given a the most wonderful of spouses, two beautiful children, family and friends, the privilege to teach theology at a good and courageous Catholic University. In short, I have more than I ever even knew to dream was possible. This is all that I could want.

Third, I actually did not write American Pope because I believed that Hahn was wrong in his theological positions. To be clear, I do believe that Hahn is wrong about certain of his beliefs, but the entire community of Catholic theologians is predicated on the notion that we find our theological beliefs in conflict. And those of us who work in the academy work within the context of that conflict in the hopes that in so doing we can together come closer to the truth. American Pope, then, is not about which of Hahn’s beliefs I happen to regard as incorrect.

Rather, I wrote American Pope because when I engage Hahn’s theological contributions I find a conviction in his own thought that allows for no other. In Hahn’s Catholic world, there is but one approach, one set of truths, one way to read the scriptures, and one way to live in the world – Hahn’s. The reason that I decided to write the book is because what I found in the works of Scott Hahn was the same fundamentalist certainty of my past. The church of my childhood was one that divided the world between those who thought like them on the one hand and evil on the other. In that world, there was no place for the radical grace, hospitality, and humility that I saw in the person of Jesus Christ and the Church he established. I wrote American Pope because I saw in Hahn’s claims of exegetical simplicity, epistemological certainty, and moral clarity the same fundamentalist hubris that poisoned my past.

My faith is not certain. I am insufficient. But I am better, made whole, perennially optimistic from within my brokenness because of the goodness of the people I love. And, miraculously, ridiculously, in the story of Catholicism throughout human history I find a place for me. I wrote American Pope because I am a sinner who walks with a community of sinners always in the work of being saved by a grace we neither deserve nor will ever fully understand. I wrote it because the working out of Catholic faith in fear and trembling will always be our present and never a forgotten part of our distant past.

Norman Vincent Peale, discouraged by the onslaught of criticism he was receiving, said that he received a letter from his father. His father told him, in essence, “Don’t let the “b……’s get you down.” I can’t remember the source for this story, but I have retained it in my sermonic memory bank. I find that it gives me consolation when I’m attacked by Ken Ham’s followers. My own father told me not to worry about criticism. He told me, “Son, you will be criticized. All you can control is what you are criticized for saying, doing, and believing.” You are being criticized for being a truth-teller. Express gratitude for all of it. The world does not look the same to the angry as it does to the grateful. Allow me the privilege of “holding you up,” like an ancient Aaron or Hur. You are among the blessed of the Lord.

Rodney Kennedy, your father is awesome. Thank you for sharing his encouraging words to you with us. To Sean Swain Martin PhD, I will be buying your book. Keep up the good work Sean: for our good and the good of all God’s holy Church.

Thank you for the kind words, friend. They mean more than you could know. And I hope my book doesn’t disappoint.

I have not read your book yet but I appreciate coming across your perspective. I am a protestant (raised non denom/fundimentalist) who is considering joining the Catholic church. In looking for resources to learn more about Catholic thought I ran across Scott Hahn and was unpleasantly reminded of the many “heros” of the neo reformed movement like John Macgarthur and others. I walked away from the Fundamentalism was raised with a long time ago and I have been very afraid that the current trend of the American Catholic church might be more of the same. Can you recommend some other resources than Dr. Hahn and his ilk to learn about the Church?

Thank you, Rod. This is wonderful. I don’t know how you all do it engaging the Ken Ham folks (although I’m starting to learn!) but it is so important. This is not an easy field that we have chosen to engage but I have only become increasingly convinced through this experience that it is the most central issue in our Christian world today. I honestly don’t know where this all is going to land but I am glad for the community of folks I have found (through the Trollingers mostly, God bless them) to walk this path with. I really appreciate the support and I hope that one day we can meet each other over a beer with Bill and Sue. Peace and all good.

Sean Martin, I have not read your book but the whole EWTN crowd sometimes acts like they know more than Jesus. it makes me cry because they obv love the Eucharist and they have so much to offer…but they think they love Jesus better or more worthily than others…the smugness is painful and heartbreaking..perfect icons of pharisee who leaves temple unjustified..and God knows how many other hearts are broken by their smarminess. They descend to the level of those they would correct in charity. I think Arroyo and Hahn etc feel they must defend the church against liberal apostates, sort of “gallantry in shining armor” for Mother Angelica the “damsel in distress” kind of thing. does that make sense to you? I too am in my senior year of university, though I have always been a “Catholic” in the Rosary/Mass/Eucharist sense, the essence of Jesus is love, and eternal life for all. Why would he die to save people from woe, and then condemn? Hello? It’s not logical.There is no Jew nor Greek and there is no condemnation in mercy…

Thank you for commenting! This is what I find so heartbreaking about the current state of Catholic fundamentalism. It is clear to me that what drives the vast majority of Catholics remains a deep love for Christ and the Church. With so much of our world and country in turmoil, however, the desire for some kind of stability, some kind of sure ground, leads some to try to simplify that which is inherently complex. The mysterious and endless love of God entails that we will never fully comprehend the depths or breadth of God’s goodness. When we try to define God’s love to determine the limits, that is, to determine who is outside of God’s grace, we lessen what has been revealed to be infinite. My understanding of Catholicism is what you discussed. I am called, not to be judge, jury, and executioner, but simply to love. When Jesus gives the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats, what divides the goats from the sheep is not their unwillingness to “stand for truth” but rather their lack of love in the form of feeding those who are hungry, giving clothes to those who are naked, and providing shelter to those without. As Francis said just this week on his trip to Canada, “ [The Church is] the place where reality is always superior to ideas.” Or as Jesus said, “Do you love me? Then feed my sheep.” Not “Do you love me? Then fight tooth and nail concerning correct theology.” Keep fighting the good fight, which is loving all and walking with those who are alone.

Sean

I do not know about the positives or negatives on your book – from the emotional view that you indicate. I am curious as to the reviews of your book from the scholarly and academic perspective from other reviewers. Francis J. Beckwith and Trent Horn are two reviews who disagree with your book but seem to have the knowledge regarding their dispute and not one based on emotions. I would love for you to sit down with Trent Horn and discuss your book and how your definition of being a “Fundamentalist” is so different than his understanding. I am sure Trent would welcome a long discussion on this issue and your book. His YouTube review is 1 hour in length and it would be interesting to hear the both of you discuss the issues in your book. Thanks.

Hi Mike, thank you for commenting! Currently, I know of several academic reviews that are in progress but none that have been published yet. I have both read Francis Beckwith’s review and watched Trent Horn’s discussion. Given what I’ve known of their backgrounds and theological perspectives, I was not surprised to see that they both strongly disliked my book. Most of what they claimed in their respective reviews I disagree with and feel that I address fully in my discussion but I am committed to being receptive to all responses to American Pope so that I can learn from both its strengths and its weakness to be a better theologian and better Catholic in the future. As to sitting down with either Beckwith or Horn, I would be happy to talk theology and my book with anyone who would want to. What I have no interest in whatsoever is to engage in debate. As David Hume says, “Truth springs forth from disagreement between friends.” And in that spirit, I would be more than happy to discuss the merits and shortcomings of my perspective with either of them (or any other reviewer!) I will accept any opportunity to walk together, rather than pushing against, towards Christ’s infinite goodness.

Sean

I agree with you regarding not having a debate. I’ve seen and been a part of too many debates and realize they serve little purpose. Discussions are to hear and understand the other person’s point of view and debates are to convince the people listening to the debate with little regard to the other debater. Thanks for replying to my comment.